Showing posts with label history. Show all posts

Showing posts with label history. Show all posts

Saturday, April 25, 2009

Historical Parallels

"I was just following orders." Such was the excuse offered by many Nazi military and political underlings later put on trial for their actions during the Second World War. This "Nuremberg defense" was judged then -- and has been repeatedly judged since -- as possessing little if any moral or legal validity; the military academy at West Point, for example, teaches that the obedience necessary to any effective fighting force does NOT mean that an American infantryman must sacrifice his or her own moral code, that soldiers must do whatever their commanders insist, no questions asked. Why should employees of the CIA be held to lesser standards? Yes, those who drafted the policies legitimating waterboarding, prolonged sleep-deprivation, and other practices now deemed immoral, illegal, or both should bear primary culpability for their subsequent implementation. And yes, the fight against terrorism has far more to recommend it -- morally and otherwise -- than an attempt to exterminate an entire people. But to condemn the architects of a given policy while, in effect, condoning the individuals who actually executed that policy seems ethically somewhat dubious: a real-life murderer, after all, may be sentenced to death, while someone who merely plots murder may win many a parlor game centered around killing. If torture is wrong, then anyone who acted as though they believed differently, whether they wielded the thumbscrews themselves or else encouraged others to do so, should be punished. If torture is acceptable (as indeed it may be in certain cases), neither promulgators nor practitioners deserve censure. Unless, of course, like Alfred Doolittle in Bernard Shaw's Pygmalion, you believe that the same moral rules need not apply to the same groups of people (e.g., "the leaders" and "the led").

Thursday, April 9, 2009

JOHN Q. PUBLIC, 1912(?) - 2009

John Q. Public died this morning after a long and painful illness. He was approximately 97 years old.

Authorities have thus far refused to disclose either the precise cause or the exact location of Mr. Public's death. The deceased, however, is known to have been afflicted for many years with an especially severe case of encephalitis lethargica. The same affliction makes it unlikely for the deceased to have moved anywhere from the site of his last confirmed residence, a sanatorium near Lake Placid in upstate New York.

A lifelong bachelor and, indeed, something of a recluse during his later years, Mr. Public leaves no known legitimate descendants -- the vociferous claims of several prominent contemporary politicians to the contrary notwithstanding.

Born within six months either way of the sinking of the Titanic in April 1912, John Public -- the distinctive Q came later -- first attracted widespread notice upon the August 1914 outbreak of "the war to end all wars" (i.e., World War I). Photographs from that period reveal a patriotic spirit no less ubiquitous than infantile: now in Trafalgar Square waving the Union Jack, now at the Brandenburg Gate donning a miniature spiked helmet, now marching (or, rather, toddling) down the Champs Elysees to the (probable) accompaniment of the Marseillaise. How this prepubescent incarnation of seemingly kaleidoscopic nationalism could fly so quickly from one warring party to the next in the age before air travel remains a mystery, as does the original parentage of the child himself. Rarely, in any event, has an orphan of such uncertain antecedents found so many strangers eager to adopt him as one of their own. By 1917 even the United States, increasingly loath to open its borders to anyone whose name was not unmistakably Anglo-Saxon (or at least Anglo-Norman), was prepared to take in young Johnny Public -- who as a de facto if not de jure American citizen would one day take in some of the most powerful members of his newfound "family," along with a good many of his erstwhile "relatives" elsewhere.

That ironic turnabout, however, lay well in the future. Through the 1920s and into the following decade, young John Public kept a generally low profile. While from time to time he could be spotted at baseball games, movie palaces, speakeasies, and other venues popular with his larger, more amorphous namesake, the future icon of indiscriminate inclusiveness is himself invisible, for the most part, among the myriad individuals self-consciously striving to epitomize the epoch to which they all professed to belong. For the adolescent Public, as for the bulk of his contemporaries, the Roaring Twenties was a period of physical growth, social (mal)adjustment, behavioral experimentation -- a period, in short, of flexing that "power without responsibility" which a famous English writer once labeled the "prerogative" of prostitutes and press lords. (At the height of the Cold War decades later, it was charged that Mr. Public -- by then, of course, a well-established Establishment Figure -- had as a teenager been kidnapped by "Leninist agents" to serve the still somewhat shaky Bolshevik regime; but research among recently released Russian archives has thus far failed to corroborate this particular charge sgainst America's former archenemy.) Nor did the onset of the Great Depression add much to young Public's public stature. Though millions were united as never before in a common quest for economic salvation, economic hardship simultaneously weakened average individuals' willingness to share the sought-after prosperity with anyone not quite as average as themselves. And John Public in the 1930s possessed neither the emotional nor the practical wherewithal to bridge these peersistent demographic rifts through the force of his own exemplary unexceptionality.

Pearl Harbor proved the making of John Public. Whether -- in common with so many of his adopted conmpatriots -- he instinctively volunteered his services in the wake of the Japanese attack, or whather he was somehow coopted by the Roosevelt administration (via, say, a threat of deportation to one of the countless other countries -- including Japan -- which claimed him as a native son), remains a matter of dispute among historians. What is undeniable is the speed with which the outwardly nondescript Public -- not yet thirty years old, and languishing in apparently contented obscurity since the heady days of the previous global armageddonn -- came to embody the fears and hopes, needs and desires, passions and aversions of the entire country (pacifists, Axis sympathizers, and diehard isolationist Republicans excepted). Like Stainbeck's Tom Joad, only on a much wider scale, the face and figure of John Public could be seen everywhere a (white, Christian, American) man was in trouble, now exhorting the troops in the Pacific to show their Japanese foes even less mercy than the Germans, now reminding the folks back home that the slice of cheese or dollop of butter they sacrficed today would help fortify their boys in the field tomorrow, now at the side of the president himself urging him to be as "tough" with the Soviets as he was with the Jews. To what extent John Public actually changed the course of the war is a moot question: historical cause and effect are too complex to be explicable solely with reference to this or that individual, even one as protean as Mr. Public. But by war's end policymakers, generals, journalists, diplomats, and Hollywood moguls were all toasting "J.P." as the single most important contributor to Allied victory. So clamorous did the applause become, in fact, that its recipient felt constrained to adopt a middle initial -- the better to sustain his firm denial whenever accosted with a demand to know if he were "that John Public."

Be that as it may, the postwar years saw the apotheosis of John Q. Public -- and not only as an entry in the dictionary. Reporters sought his views on everything from atom smashers to Barbie dolls to capital punishment; advertisers solicited his endorsement -- free or otherwise -- of their products; government office-holders of all political stripes regularly invoked his name in support of measures under attack by less favored members of the electorate. Nor, it must be emphasized, was John Q. Public himself a passive participant in this seeming exploitation of his persona. On the contrary, his very malleability rendered him an ideal spokesman for a society where differences of opinion or taste or purpose were as much a part of the landscape as the chameleon in New England. Any stance he might take one week could be abandoned the next, with nnobody being the wiser -- or, at any rate, prepared to risk the consequences (e.g., loss of office) a demonstration of their newfound wisdom might incur. No wonder Life magazine titled its -- admiring -- 1957 profile of Mr. Public: "Move Aside, Lon Chaney! Here's a Man of More than a Thousand Faces!"

A comparable article could probably not have been written ten years later. Growing divisiveness over Vietnam, civil rights, the respective merits of heroin vs. marijuana, and other vital issues of the day led to larger cleavages (i.e., within the American polity) unbridgeable -- or so it appeared -- even by so consummate a master of consistent inconsistency as John Q. Public. Yet Mr. Public's public standing remained high enough to allow him to retain the ear, the resepect, and the confidence of groups across the occupational, generational, and ideological spectrum. The White House may have been at daggers drawn wih the Fourth Estate, parents may have thought their children revolting and vice versa, integrationists and segregationists may have kept their distance from each other -- but all were at one in insisting that John Q. Public was indeed on their side of the barricades. Thus the turbulent sixties ended (c. 1974) with Mr. Public the supreme symbol of a unity from which none were excluded except the inorrigibly unique.

Symbols, however, are prone to outlive their usefulness, to be discarded once whatever they symbolize either no longer exists or, conversely, exists in such plenitude as to obviate all need for any "external" representation thereof. The 1980s in the United States witnessed a rare conjunction of both phenomena, a newly earnest solicitude for the first person singular flourishing alongside an equally impassioned determination to make all one's neighbors as oneself. Caught between these competing yet complementary forces, John Q. Public became superfluous. Though he continued to draw crowds on Capitol Hill, in the anterooms of Madison Avenue, and at American Legion outposts around the country, general neglect gradually impelled Mr. Public to withdraw from the public arena entirely. His last public appearance was at a patriotic rally outside Oswego on 12 September 2001 -- a rally at which Mr. Public was verbally assaulted for not bellowing the national anthem as lustily as everyone else; only his obvious age and frailty saved the octogenerian warbler from more tangible signs of hostility. Such is the gratitude that democracies from time immemorial have been wont to bestow upon those who most nearly exemplify the democratic ideal.

One may, of course, legitimately wonder how many would have noticed John Public's absence or presence at any point in his career. Seldom has a figure of such widespread and protracted renown left so meager a record of personal identity: there is no birth certificate, no school diploma, no driver's license, no library card, no bankbook, not even a single photograph to accompany the present obituary. Interviews, it is true, abound, but -- like the periodic references to Mr. Public in presidents' and other ostensible leaders' memoirs -- they are too contradictory to permit a definitive assessment of their subject's character and thinnking, while rumors of a massive, "tell-all" autobiography remain unsubstantiated. Someday, no doubt, an especially enterprising sociologist, political scientist, anthropologist, and/or gossip columnist will attempt to piece together the full story of this remarkable individual who paradoxically transcended mediocrity by embracing it. Yet in the final analysis John Q. Public's name and fame rest on a foundation far more durable than the printed word -- the same foundation that lent immortality to Shakespeare's "poor player." For few indeed have beem able to vent greater "sound and fury" than an aroused Mr. Public -- and fewer still, we daresay, could match Mr. Public in achieving so much of such lasting insignificance.

Burial services for the deceased will be private. A fund has been established, however, to erect a monument to Mr. Public at one or another of the literally innumerable localities where he was active. Interested parties may send their tax-deductible contributions to: The JQP Memorial Foundation, c/o Vox Populi, Inc., P.O. Box 666a, Grover's Corner, NH, 01212.

Authorities have thus far refused to disclose either the precise cause or the exact location of Mr. Public's death. The deceased, however, is known to have been afflicted for many years with an especially severe case of encephalitis lethargica. The same affliction makes it unlikely for the deceased to have moved anywhere from the site of his last confirmed residence, a sanatorium near Lake Placid in upstate New York.

A lifelong bachelor and, indeed, something of a recluse during his later years, Mr. Public leaves no known legitimate descendants -- the vociferous claims of several prominent contemporary politicians to the contrary notwithstanding.

Born within six months either way of the sinking of the Titanic in April 1912, John Public -- the distinctive Q came later -- first attracted widespread notice upon the August 1914 outbreak of "the war to end all wars" (i.e., World War I). Photographs from that period reveal a patriotic spirit no less ubiquitous than infantile: now in Trafalgar Square waving the Union Jack, now at the Brandenburg Gate donning a miniature spiked helmet, now marching (or, rather, toddling) down the Champs Elysees to the (probable) accompaniment of the Marseillaise. How this prepubescent incarnation of seemingly kaleidoscopic nationalism could fly so quickly from one warring party to the next in the age before air travel remains a mystery, as does the original parentage of the child himself. Rarely, in any event, has an orphan of such uncertain antecedents found so many strangers eager to adopt him as one of their own. By 1917 even the United States, increasingly loath to open its borders to anyone whose name was not unmistakably Anglo-Saxon (or at least Anglo-Norman), was prepared to take in young Johnny Public -- who as a de facto if not de jure American citizen would one day take in some of the most powerful members of his newfound "family," along with a good many of his erstwhile "relatives" elsewhere.

That ironic turnabout, however, lay well in the future. Through the 1920s and into the following decade, young John Public kept a generally low profile. While from time to time he could be spotted at baseball games, movie palaces, speakeasies, and other venues popular with his larger, more amorphous namesake, the future icon of indiscriminate inclusiveness is himself invisible, for the most part, among the myriad individuals self-consciously striving to epitomize the epoch to which they all professed to belong. For the adolescent Public, as for the bulk of his contemporaries, the Roaring Twenties was a period of physical growth, social (mal)adjustment, behavioral experimentation -- a period, in short, of flexing that "power without responsibility" which a famous English writer once labeled the "prerogative" of prostitutes and press lords. (At the height of the Cold War decades later, it was charged that Mr. Public -- by then, of course, a well-established Establishment Figure -- had as a teenager been kidnapped by "Leninist agents" to serve the still somewhat shaky Bolshevik regime; but research among recently released Russian archives has thus far failed to corroborate this particular charge sgainst America's former archenemy.) Nor did the onset of the Great Depression add much to young Public's public stature. Though millions were united as never before in a common quest for economic salvation, economic hardship simultaneously weakened average individuals' willingness to share the sought-after prosperity with anyone not quite as average as themselves. And John Public in the 1930s possessed neither the emotional nor the practical wherewithal to bridge these peersistent demographic rifts through the force of his own exemplary unexceptionality.

Pearl Harbor proved the making of John Public. Whether -- in common with so many of his adopted conmpatriots -- he instinctively volunteered his services in the wake of the Japanese attack, or whather he was somehow coopted by the Roosevelt administration (via, say, a threat of deportation to one of the countless other countries -- including Japan -- which claimed him as a native son), remains a matter of dispute among historians. What is undeniable is the speed with which the outwardly nondescript Public -- not yet thirty years old, and languishing in apparently contented obscurity since the heady days of the previous global armageddonn -- came to embody the fears and hopes, needs and desires, passions and aversions of the entire country (pacifists, Axis sympathizers, and diehard isolationist Republicans excepted). Like Stainbeck's Tom Joad, only on a much wider scale, the face and figure of John Public could be seen everywhere a (white, Christian, American) man was in trouble, now exhorting the troops in the Pacific to show their Japanese foes even less mercy than the Germans, now reminding the folks back home that the slice of cheese or dollop of butter they sacrficed today would help fortify their boys in the field tomorrow, now at the side of the president himself urging him to be as "tough" with the Soviets as he was with the Jews. To what extent John Public actually changed the course of the war is a moot question: historical cause and effect are too complex to be explicable solely with reference to this or that individual, even one as protean as Mr. Public. But by war's end policymakers, generals, journalists, diplomats, and Hollywood moguls were all toasting "J.P." as the single most important contributor to Allied victory. So clamorous did the applause become, in fact, that its recipient felt constrained to adopt a middle initial -- the better to sustain his firm denial whenever accosted with a demand to know if he were "that John Public."

Be that as it may, the postwar years saw the apotheosis of John Q. Public -- and not only as an entry in the dictionary. Reporters sought his views on everything from atom smashers to Barbie dolls to capital punishment; advertisers solicited his endorsement -- free or otherwise -- of their products; government office-holders of all political stripes regularly invoked his name in support of measures under attack by less favored members of the electorate. Nor, it must be emphasized, was John Q. Public himself a passive participant in this seeming exploitation of his persona. On the contrary, his very malleability rendered him an ideal spokesman for a society where differences of opinion or taste or purpose were as much a part of the landscape as the chameleon in New England. Any stance he might take one week could be abandoned the next, with nnobody being the wiser -- or, at any rate, prepared to risk the consequences (e.g., loss of office) a demonstration of their newfound wisdom might incur. No wonder Life magazine titled its -- admiring -- 1957 profile of Mr. Public: "Move Aside, Lon Chaney! Here's a Man of More than a Thousand Faces!"

A comparable article could probably not have been written ten years later. Growing divisiveness over Vietnam, civil rights, the respective merits of heroin vs. marijuana, and other vital issues of the day led to larger cleavages (i.e., within the American polity) unbridgeable -- or so it appeared -- even by so consummate a master of consistent inconsistency as John Q. Public. Yet Mr. Public's public standing remained high enough to allow him to retain the ear, the resepect, and the confidence of groups across the occupational, generational, and ideological spectrum. The White House may have been at daggers drawn wih the Fourth Estate, parents may have thought their children revolting and vice versa, integrationists and segregationists may have kept their distance from each other -- but all were at one in insisting that John Q. Public was indeed on their side of the barricades. Thus the turbulent sixties ended (c. 1974) with Mr. Public the supreme symbol of a unity from which none were excluded except the inorrigibly unique.

Symbols, however, are prone to outlive their usefulness, to be discarded once whatever they symbolize either no longer exists or, conversely, exists in such plenitude as to obviate all need for any "external" representation thereof. The 1980s in the United States witnessed a rare conjunction of both phenomena, a newly earnest solicitude for the first person singular flourishing alongside an equally impassioned determination to make all one's neighbors as oneself. Caught between these competing yet complementary forces, John Q. Public became superfluous. Though he continued to draw crowds on Capitol Hill, in the anterooms of Madison Avenue, and at American Legion outposts around the country, general neglect gradually impelled Mr. Public to withdraw from the public arena entirely. His last public appearance was at a patriotic rally outside Oswego on 12 September 2001 -- a rally at which Mr. Public was verbally assaulted for not bellowing the national anthem as lustily as everyone else; only his obvious age and frailty saved the octogenerian warbler from more tangible signs of hostility. Such is the gratitude that democracies from time immemorial have been wont to bestow upon those who most nearly exemplify the democratic ideal.

One may, of course, legitimately wonder how many would have noticed John Public's absence or presence at any point in his career. Seldom has a figure of such widespread and protracted renown left so meager a record of personal identity: there is no birth certificate, no school diploma, no driver's license, no library card, no bankbook, not even a single photograph to accompany the present obituary. Interviews, it is true, abound, but -- like the periodic references to Mr. Public in presidents' and other ostensible leaders' memoirs -- they are too contradictory to permit a definitive assessment of their subject's character and thinnking, while rumors of a massive, "tell-all" autobiography remain unsubstantiated. Someday, no doubt, an especially enterprising sociologist, political scientist, anthropologist, and/or gossip columnist will attempt to piece together the full story of this remarkable individual who paradoxically transcended mediocrity by embracing it. Yet in the final analysis John Q. Public's name and fame rest on a foundation far more durable than the printed word -- the same foundation that lent immortality to Shakespeare's "poor player." For few indeed have beem able to vent greater "sound and fury" than an aroused Mr. Public -- and fewer still, we daresay, could match Mr. Public in achieving so much of such lasting insignificance.

Burial services for the deceased will be private. A fund has been established, however, to erect a monument to Mr. Public at one or another of the literally innumerable localities where he was active. Interested parties may send their tax-deductible contributions to: The JQP Memorial Foundation, c/o Vox Populi, Inc., P.O. Box 666a, Grover's Corner, NH, 01212.

Tuesday, March 31, 2009

Why I am a Zionist

Deeply aware of the harmful consequences wrought throughout history by unflinching adherence to this or that particular ideological creed (political, economic, theological, artistic, whatever), I have little sympathy -- intellectual or otherwise -- with "isms" of any sort. Far better, I think, to consider situations and problems on a case-by-case basis rather than try to subordinate everyithing to the kind of ideological strait-jacket that most isms represent. To this longstanding distrust of ideational systematization, however, I make two exceptions. One is individualism. The other is Zionism. And my belief in individualism is subject to all sorts of constraints.

Behind Theodor Herzl's push for a Jewish state lay two (distinct but overlapping) motives. One was his belief that the Jewish people, if joined together in their own community and allowed to give full vent to to all their abilities and aspirations, could make even more indelible contributions than they already had to human civilization. Antisemitism comprised the other, more immediately visible spur to Herzl's vision. It was the Dreyfus Affair in France which convinced Herzl that Jews could never be truly secure lving among the Gentiles, that only a state of their own could guarantee the Jews' survival, literal and otherwise. Regarding the notion of a Jewish "collectivity" whose existence would somehow benefit the whole human race I am agnostic at best; when it comes to creativity and genius, lving among one's own "kind" is often far more stultifying to individual creativity and genius than dwelling amidst strangers and enemies (as the Jewish experience itself amply attests). But Herzl's prognosis of the antisemitism which makes a Jewish state a vital necessity rather than just a desirable luxury remains all too accurate.

While I have never encountered any antisemitic remarks directed against me personally, evidence of antisemitism -- or, at the very least, of an inclination to view Jews as somehow different from, and by implication inferior to, everyone else -- has not been lacking in my experience. More memorable indications include the following:

(1) One of my students in Hungary, in an essay dealing with the subject of money, repeated the old canard about Jews controlling most of the world's finances. And a leading historian in the university department where I taught insisted that the Jews themselves -- by virtue of their wealth as well as their predominance in certain fields such as law and journalism -- bore the lion's share of responsibility for the Nazi onslaught against them. (That most Magyars continue to attribute the actual slaughter of 400,000+ Hungarian Jews in 1944-45 to the fewer than 300 Germans who entered the country in mid-1944, rather than to the thousands upon thousands of the Germans' willing Hungarian helpers, is, I believe, a reflection less of antisemitism than of nationalism. After all, today's Hungarians show a similar reluctance to criticize their forebears' discriminatory "magyarization" policy of the nineteenth century.)

(2) At a two-hour seminar I conducted on antisemitism, students of Latvia's leading university revealed a veritable array of standard antisemitic stereotypes: Jews were unduly clannish and didn't want to be friends with anyone else, Jews cared only about making money, Jews were averse to working the land (i.e., as farmers), Jews felt no attachmment to the countries where they lived, etc., etc., etc. (It was while living in Latvia, too, that I witnessed vestigial antisemitism from another, far more respected source, the BBC, whose coverage of the then-latest Israeli-Palestinian clash was hopelessly one-sided. An interview with a Palestinian spokesperson began with a civil question about why they were fighting Israel, while an immediately subsequent interview with the Israli Defense Minister began thus: "So, Mr. Minister, how many Palestinians did you kill today?" To be fair, though, it was another BBC broadcaster who reported starker proof yet of Europe's still vibrant antisemitic tradition: an editorial cartoon in Madrid's leading newspaper which depicted an image of Jesus above a Bethlehem church that Israli soldiers had fire upon in an effort to dislodge several Palestinian gunmen who had taken refuge there. The caption below the Jesus drawing read: "My God, my God, have they come to crucify me again?" Old ways of non-thinking do die hard, don't they?)

(3) In an (outwardly civil) argument on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, the head of the Thai branch of an internationally renowned NGO told me that the Jews did not need a homeland of their own, that Jews who were persecuted in places like Russia or Syria could be helped by those Jewish moguls who dominated finance, government, and the media in the West.

(4) More than one Russian I met during my brief stay in Kazan referred -- casually, not maliciously -- to "Jews" and "Russians," as though a person could never be both. (This, however, was far less annoying to me than certain remarks made by a guest American lecturer -- an expert on early modern Polish Jewry -- during one of her scheduled public talks at the university. To a student who asked her assessment of Russian antisemitism past and present, the professor replied that reports of such were grossly exaggerated, that [for example] not all the czars were against the Jews [though precisely who she had in mind was never clarified], that she herself -- with a discernibly Jewish last name -- had been treated with the utmost courtesy and respect by all the Russians she had met during her trip. One harlly needs a PhD to spout -- or spot -- such nonsense.)

(5) In our first -- and last -- sustained conversation on politics, the woman whose house I lived in during my recent stay in San Francisco said that "the Zionists" were to blame for blocking the arms embargo which would've prevented Hitler from launching war in 1939. That such a claim rested on more (or should I say less?) than a singularly perverse non-reading of history was later demonstrated by (among other remarks) the woman's scathing denunciation of "the Zionist/Jewish scum" who had made her life so miserable. (Or so she loudly proclaimed in the course of a telephone conversation the bulk of which, mercifully, I could not overhear.)

(6) In talking about Israel's recent attack on Gaza, one of my newfound acquaintances here in Korea has admitted he hates Jews -- less on account of Israeli actions than because of some bad dealings he (or his company) had with an overseas Jewish financier. Further conversation seems to have changed his mind, at least as far as Israel is concerned (he freely admitting his ignorance on that subject). But to what extent he still harbors a vestigial antipathy toward "the Jewish race" I cannot say with any certainty.

Individually, each of these episodes betokens little but stupidity and/or bigotry on the part of its protagonist. And even collectively, they cannot be said to signify anything so ominous as a "trend" or a "forecast." But they do serve as sharp reminders that the antisemitism of which Herzl spoke over a century ago remains alive and well, even in places where the "Jewish question" has never really existed.

Which is not to suggest that we are on the verge of a second Shoah. For reasons having more to do with geopolitics than with humanitarianism, no sane person or government today seriously contemplates attempting to finish the job Hitler began; had the people of Darfur or the victims of the Khmer Rouge or the Muslims of Bosnia possessed nuclear weapons, the rest of the world would no doubt have looked upon their respective plights with somewhat less "blinded" vision. But personal experience as well as extensive reading has convinced me that nary a gentile eye would blink if the Jews just "disappeared," either figuratively (i.e., through assimilation) or literally. Thus I regard the continued existence of Israel as a moral no less than a strategic imperative. That Israel is also a haven of individualism represents merely another point in its favor.

Behind Theodor Herzl's push for a Jewish state lay two (distinct but overlapping) motives. One was his belief that the Jewish people, if joined together in their own community and allowed to give full vent to to all their abilities and aspirations, could make even more indelible contributions than they already had to human civilization. Antisemitism comprised the other, more immediately visible spur to Herzl's vision. It was the Dreyfus Affair in France which convinced Herzl that Jews could never be truly secure lving among the Gentiles, that only a state of their own could guarantee the Jews' survival, literal and otherwise. Regarding the notion of a Jewish "collectivity" whose existence would somehow benefit the whole human race I am agnostic at best; when it comes to creativity and genius, lving among one's own "kind" is often far more stultifying to individual creativity and genius than dwelling amidst strangers and enemies (as the Jewish experience itself amply attests). But Herzl's prognosis of the antisemitism which makes a Jewish state a vital necessity rather than just a desirable luxury remains all too accurate.

While I have never encountered any antisemitic remarks directed against me personally, evidence of antisemitism -- or, at the very least, of an inclination to view Jews as somehow different from, and by implication inferior to, everyone else -- has not been lacking in my experience. More memorable indications include the following:

(1) One of my students in Hungary, in an essay dealing with the subject of money, repeated the old canard about Jews controlling most of the world's finances. And a leading historian in the university department where I taught insisted that the Jews themselves -- by virtue of their wealth as well as their predominance in certain fields such as law and journalism -- bore the lion's share of responsibility for the Nazi onslaught against them. (That most Magyars continue to attribute the actual slaughter of 400,000+ Hungarian Jews in 1944-45 to the fewer than 300 Germans who entered the country in mid-1944, rather than to the thousands upon thousands of the Germans' willing Hungarian helpers, is, I believe, a reflection less of antisemitism than of nationalism. After all, today's Hungarians show a similar reluctance to criticize their forebears' discriminatory "magyarization" policy of the nineteenth century.)

(2) At a two-hour seminar I conducted on antisemitism, students of Latvia's leading university revealed a veritable array of standard antisemitic stereotypes: Jews were unduly clannish and didn't want to be friends with anyone else, Jews cared only about making money, Jews were averse to working the land (i.e., as farmers), Jews felt no attachmment to the countries where they lived, etc., etc., etc. (It was while living in Latvia, too, that I witnessed vestigial antisemitism from another, far more respected source, the BBC, whose coverage of the then-latest Israeli-Palestinian clash was hopelessly one-sided. An interview with a Palestinian spokesperson began with a civil question about why they were fighting Israel, while an immediately subsequent interview with the Israli Defense Minister began thus: "So, Mr. Minister, how many Palestinians did you kill today?" To be fair, though, it was another BBC broadcaster who reported starker proof yet of Europe's still vibrant antisemitic tradition: an editorial cartoon in Madrid's leading newspaper which depicted an image of Jesus above a Bethlehem church that Israli soldiers had fire upon in an effort to dislodge several Palestinian gunmen who had taken refuge there. The caption below the Jesus drawing read: "My God, my God, have they come to crucify me again?" Old ways of non-thinking do die hard, don't they?)

(3) In an (outwardly civil) argument on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, the head of the Thai branch of an internationally renowned NGO told me that the Jews did not need a homeland of their own, that Jews who were persecuted in places like Russia or Syria could be helped by those Jewish moguls who dominated finance, government, and the media in the West.

(4) More than one Russian I met during my brief stay in Kazan referred -- casually, not maliciously -- to "Jews" and "Russians," as though a person could never be both. (This, however, was far less annoying to me than certain remarks made by a guest American lecturer -- an expert on early modern Polish Jewry -- during one of her scheduled public talks at the university. To a student who asked her assessment of Russian antisemitism past and present, the professor replied that reports of such were grossly exaggerated, that [for example] not all the czars were against the Jews [though precisely who she had in mind was never clarified], that she herself -- with a discernibly Jewish last name -- had been treated with the utmost courtesy and respect by all the Russians she had met during her trip. One harlly needs a PhD to spout -- or spot -- such nonsense.)

(5) In our first -- and last -- sustained conversation on politics, the woman whose house I lived in during my recent stay in San Francisco said that "the Zionists" were to blame for blocking the arms embargo which would've prevented Hitler from launching war in 1939. That such a claim rested on more (or should I say less?) than a singularly perverse non-reading of history was later demonstrated by (among other remarks) the woman's scathing denunciation of "the Zionist/Jewish scum" who had made her life so miserable. (Or so she loudly proclaimed in the course of a telephone conversation the bulk of which, mercifully, I could not overhear.)

(6) In talking about Israel's recent attack on Gaza, one of my newfound acquaintances here in Korea has admitted he hates Jews -- less on account of Israeli actions than because of some bad dealings he (or his company) had with an overseas Jewish financier. Further conversation seems to have changed his mind, at least as far as Israel is concerned (he freely admitting his ignorance on that subject). But to what extent he still harbors a vestigial antipathy toward "the Jewish race" I cannot say with any certainty.

Individually, each of these episodes betokens little but stupidity and/or bigotry on the part of its protagonist. And even collectively, they cannot be said to signify anything so ominous as a "trend" or a "forecast." But they do serve as sharp reminders that the antisemitism of which Herzl spoke over a century ago remains alive and well, even in places where the "Jewish question" has never really existed.

Which is not to suggest that we are on the verge of a second Shoah. For reasons having more to do with geopolitics than with humanitarianism, no sane person or government today seriously contemplates attempting to finish the job Hitler began; had the people of Darfur or the victims of the Khmer Rouge or the Muslims of Bosnia possessed nuclear weapons, the rest of the world would no doubt have looked upon their respective plights with somewhat less "blinded" vision. But personal experience as well as extensive reading has convinced me that nary a gentile eye would blink if the Jews just "disappeared," either figuratively (i.e., through assimilation) or literally. Thus I regard the continued existence of Israel as a moral no less than a strategic imperative. That Israel is also a haven of individualism represents merely another point in its favor.

Sunday, March 8, 2009

A word of advice to Obama's critics

Read a biography of Franklin Delano Roosevelt (preferably one written by a professional historian rather than by a partisan hack). Granted, the circumstances (political, economic, international) were very different in many respects. Granted, too, the New Deal was of questionable efficacy in getting America out of the Great Depression an eventuality for which the country had to await the onset of the Second World War. But at least FDR was trying to do SOMETHING, something different from just relying on the same old nostrums (and the same old personnel) that had done so much to bring about the depression in the first place. Perhaps more importantly, Roosevelt saw the crisis confronting him as an opportunity to bring about (or at least try to bring about) certain fundamental changes in the relationship between government and society, as well as in some concrete governmental policies.

Does Obama have a comparable longer-term vision? It would seem so; indeed, one might claim that the current president, more open to contemporary realities, less hidebound by traditional constraints of class and gender and race, sees even farther than his predecessor of seven decades before. To what extent he will succeed in realizing his vision remains to be seen. But if nothing else, he offers a worthy alternative to those who prefer to seek solace in the latest biography of Herbert Hoover.

Does Obama have a comparable longer-term vision? It would seem so; indeed, one might claim that the current president, more open to contemporary realities, less hidebound by traditional constraints of class and gender and race, sees even farther than his predecessor of seven decades before. To what extent he will succeed in realizing his vision remains to be seen. But if nothing else, he offers a worthy alternative to those who prefer to seek solace in the latest biography of Herbert Hoover.

Sunday, February 8, 2009

A lifelong love affair

I fell in love with history on the same day as, though for reasons unconnected to, Richard Nixon's resignation from the White House. (Or, rather, it was reading about history that I fell in love with; the actual content of history, goodness knows, often has little "lovable" about it.) On August 9, 1974, finished (or bored) with my schoolwork and having nothing else to do, I picked up volume "C" of the World Book Encyclopedia and started browsing through it; within minutes, I was absorbed in the entry about the American Civil War. For the next two or three years I read every book I could find on the war, culminating in Shelby Foote's magnificent trilogy. Gradually, my historical interests expanded -- chronologically, geographically, thematically. While I cannot claim to be equally fascinated by every country, every era, every facet of the human experience (business and economics leave me especially uncaptivated), my interests are broad enough to preclude me from joining the ranks of the dryasdust pedants (in many disciplines besides history, of course) who have made a career (if little else) out of penning monographs that compete with each other to see which can gather the most dust on the most library shelves in the least amount of time. For better or worse, that is one competition I have neither the temperament nor the credentials to enter. More a generalist than a specialist, and more an autodidact than a creature of academe, I read whatever I think will add to my overall knowledge of the human race -- hopefully in at least a mildly felicitous fashion.

And what do I find so absorbing about history? Well, in the first place, it tells a story, a story complete with plot, setting, atmosphere, characters (even if those characters be inanimate objects like "love" or "violence" or "progress"). Focusing on people "in action," as it were, history also allows us to assess human nature on the basis of concrete observations and (David Hume notwithstanding) more or less "objective" realities. That the average human being (i.e., 99.9% of the race) has little inclination and less ability to make such assessments is itself a conclusion to be drawn from study of human history -- as is humanity's almost habitual incapacity to derive the proper lessons from the past. (And yes, these generalizations on my part are themselves open to dispute -- but only by those whose historical knowledge is limited to what they've read in the encyclopedia, or Sunday newspaper supplements, or recent monographs devoted to their particular field of expertise).

And what do I find so absorbing about history? Well, in the first place, it tells a story, a story complete with plot, setting, atmosphere, characters (even if those characters be inanimate objects like "love" or "violence" or "progress"). Focusing on people "in action," as it were, history also allows us to assess human nature on the basis of concrete observations and (David Hume notwithstanding) more or less "objective" realities. That the average human being (i.e., 99.9% of the race) has little inclination and less ability to make such assessments is itself a conclusion to be drawn from study of human history -- as is humanity's almost habitual incapacity to derive the proper lessons from the past. (And yes, these generalizations on my part are themselves open to dispute -- but only by those whose historical knowledge is limited to what they've read in the encyclopedia, or Sunday newspaper supplements, or recent monographs devoted to their particular field of expertise).

Last but not least, history offers a never-ending source of antidotes to counter the belief that we live live in either the best or the worst of all possible worlds. However great or awful today may seem, rest assured that there's always been a yesterday even more so.

And what do I find so absorbing about history? Well, in the first place, it tells a story, a story complete with plot, setting, atmosphere, characters (even if those characters be inanimate objects like "love" or "violence" or "progress"). Focusing on people "in action," as it were, history also allows us to assess human nature on the basis of concrete observations and (David Hume notwithstanding) more or less "objective" realities. That the average human being (i.e., 99.9% of the race) has little inclination and less ability to make such assessments is itself a conclusion to be drawn from study of human history -- as is humanity's almost habitual incapacity to derive the proper lessons from the past. (And yes, these generalizations on my part are themselves open to dispute -- but only by those whose historical knowledge is limited to what they've read in the encyclopedia, or Sunday newspaper supplements, or recent monographs devoted to their particular field of expertise).

And what do I find so absorbing about history? Well, in the first place, it tells a story, a story complete with plot, setting, atmosphere, characters (even if those characters be inanimate objects like "love" or "violence" or "progress"). Focusing on people "in action," as it were, history also allows us to assess human nature on the basis of concrete observations and (David Hume notwithstanding) more or less "objective" realities. That the average human being (i.e., 99.9% of the race) has little inclination and less ability to make such assessments is itself a conclusion to be drawn from study of human history -- as is humanity's almost habitual incapacity to derive the proper lessons from the past. (And yes, these generalizations on my part are themselves open to dispute -- but only by those whose historical knowledge is limited to what they've read in the encyclopedia, or Sunday newspaper supplements, or recent monographs devoted to their particular field of expertise).Last but not least, history offers a never-ending source of antidotes to counter the belief that we live live in either the best or the worst of all possible worlds. However great or awful today may seem, rest assured that there's always been a yesterday even more so.

Monday, January 26, 2009

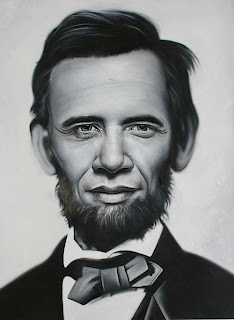

Historical Parallels

Many of late have taken to comparing Barack Obama with Abraham Lincoln, encouraged by no less a figure than the new president himself. But how many have paused to consider the possibly even greater similarity between the two men's immediate predecessors?

Many of late have taken to comparing Barack Obama with Abraham Lincoln, encouraged by no less a figure than the new president himself. But how many have paused to consider the possibly even greater similarity between the two men's immediate predecessors? To be sure, the resemblance is not exact. James Buchanan enjoyed an at least nominally distinguished career as a diplomat and senator before stepping into the Oval Office, whereas prior to 2001 George W. Bush was known chiefly as the unremarkable son of a mediocre president.

To be sure, the resemblance is not exact. James Buchanan enjoyed an at least nominally distinguished career as a diplomat and senator before stepping into the Oval Office, whereas prior to 2001 George W. Bush was known chiefly as the unremarkable son of a mediocre president. Moreover, the problems confronting Buchanan during his administration were problems of long standing, for which more than one eminent policymaker could justly claim responsibility, while the major part of Bush's maleficent legacy can rest comfortably on his shoulders alone. Then, too, Buchanan was unmarried. But nothing, absolutely nothing, ought to detract from the single biggest fact uniting the 15th U.S. president and the 43rd: both men left the country infinitely worse off than when they entered office.

Moreover, the problems confronting Buchanan during his administration were problems of long standing, for which more than one eminent policymaker could justly claim responsibility, while the major part of Bush's maleficent legacy can rest comfortably on his shoulders alone. Then, too, Buchanan was unmarried. But nothing, absolutely nothing, ought to detract from the single biggest fact uniting the 15th U.S. president and the 43rd: both men left the country infinitely worse off than when they entered office.To what extent, if any, Obama's presidential tenure will bear comparison with Lincoln's it is much too early to say. As fresh assessments of the latter continue to be put forth even today, over 150 years after his death, surely we should try to refrain from judging a man --for good or for ill -- who has held the reins of executive power for less than a week. James Buchanan, on the other hand, has been consistently deemed one of the worst U.S. presidents ever -- and this despite his insistence that history would "vindicate" him. Perhaps the record of the latest ex-president will force historians to reconsider.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)